Date

- There are 26 million refugees globally

- Half of the world’s refugees are children

- 85% of refugees are being hosted in developing countries

(Source, Amnesty International)

Every year, an estimated 500,000 people flee extreme violence and poverty in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, and head north through Mexico to find safety. The high levels of violence in the region, known as the Northern Triangle of Central America, are comparable to those in the international war zones where MSF has worked for decades.

Gang-related murders, kidnappings, extortion and sexual violence are daily facts of life. “In my country, killing is ordinary — it is as easy as killing an insect with your shoe,” said one man from Honduras, who was threatened by gangs for refusing their demand for protection money, and later shot three times.

*I did tell Fernando I planned to blog about him and this experience and he has given me his permission.

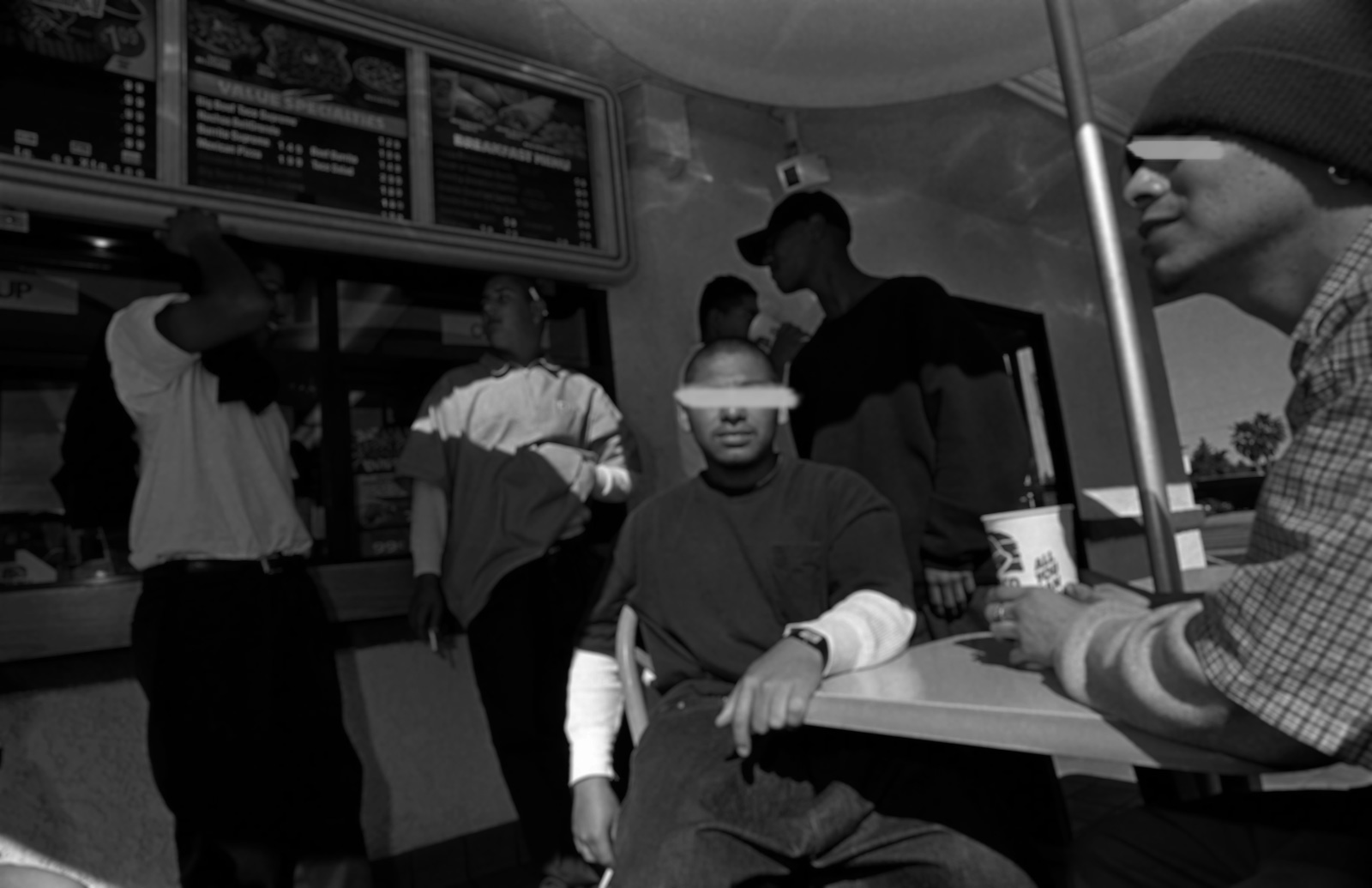

Fernando was forced to flee by the gangs. Here is a short summary from a 2019 article by Tariq Zaidi of The Guardian about the gangs in El Salvador.

There are 60,000 active gang members from the gangs Mara Salvatrucha 13 (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (La 18), and the outnumbered 52,000 Salvadoran state officers, consisting of the police, paramilitary and military forces.

The gangs’ origins can be traced to Salvadorans who fled to the US, and in particular to teens in Los Angeles. Through radicalisation via jail stints for nonviolent crimes, Salvadorans were hardened and turned to violence, establishing the methods and networks associated with MS-13. La 18, in contrast, was formed as the first multiracial, multiethnic gang in the city, and is now a mostly Central American gang.

After the civil war in El Salvador ended in 1992, US immigration policies hardened and migrants who had been convicted of crimes were sent back to El Salvador, bringing gang culture and violence to an already struggling state. Through recruitment, extortion and coercion, the gangs continued to grow in number and influence, holding ever greater control over the country.

Today, El Salvador is a paralysed state. Turf wars have split apart families, made travel impossible and crippled the government. Disappearances are common (the numbers of those disappeared are not counted in homicide statistics, understating the scale of violence) and following up with the police is not recommended – informers and moles are everywhere.

The police are always on high-alert and officers wear balaclavas to protect their identities, but attacks on the police are common. This breakdown of trust has created a uniquely problematic socio-political situation, and helps explain why for many Salvadorans the only answer is migration, usually to the north to Mexico and the US.

No Options

Fernando was forced to join a gang due to a close relative being a prominent member. The family member’s status initially afforded him the privilege of not having to participate in violence. However, after witnessing several murders he couldn’t take it anymore and fled to Mexico. Before that happened he was arrested and put in jail for being a gang member (he has an identifying mandatory tattoo that all members receive). As long as he has that tattoo he will be a target of the police. If he removes or covers it the gang would kill him and now that he has deserted, he will be killed if he ever returns.

Fernando says that gang members have been known to monitor social media and check phones of family members of deserters in order to track them down and exact revenge. For this reason, we won’t post any identifying photos of him nor use his real name.

Fernando ran with his wife to seek asylum in Mexico but because of the gang tattoo, he was denied. They decided to flee within Mexico before they could be deported to El Salvador. Fernando’s wife decided to go home to say goodbye to her family before leaving. When she arrived home she was immediately found and shot dead in the street in front of her family.

Fernando stayed in Mexico for several years where he found odd jobs but because he wasn’t legal he was frequently cheated out of his pay. He was also robbed of all his belongings 5 times in his life, both in El Salvador and Mexico. Finally, he decided his only option for a better life was to try to seek asylum in the US.

A Wrong Move

Fernando travelled with a few others to the border and crossed at a non-official entry point. They were promptly detained and when he said he wanted to seek asylum, they conducted the usual background check and he was then transferred to a detention center in San Diego. We are not certain how long this all took.

Fernando was in detention for over a year and 4 months. He filed his application for asylum, was denied, and has submitted an appeal. He believes because of his gang affiliation he will ultimately lose all appeals. We hold out hope and are doing everything we can to avoid that. More details to come in future posts but we appreciate prayers that he is granted asylum.

Asylum-seekers are put on an “asylum clock” that determines their eligibility for a work permit following their submission of an asylum application. They become eligible to file for an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) 150 days after filing a “complete” asylum application and can receive an EAD 180 days after filing a “complete” asylum application. We also discovered that an AS can call a hotline (1-800-898-7180) to check the status of their clock, as well as info on the next hearing date, asylum processing information, decision information, case appeal information, or filing information.